Was Hammond’s parole a death warrant?

Courtesy of the Madera County Historical Society

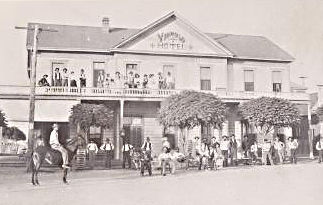

Vignolo’s Hotel nearly always had a crowd like this, especially on that day when Leonard Hammond held up its saloon in 1901.

If ever there was such a thing as a ne’er do well, Leonard Hammond must have been it. He spent 15 months in jail for a crime spree in Arizona before he came to Madera in 1901, robbed the Vignolo Hotel, and wound up behind bars.

Judge Conley sentenced him to Folsom Prison for 90 years, and that is where he would have stayed if only his mother had not come to town in 1909, begging former Sheriff William B. Thurman to sign her petition for her son’s release. Little did she know that the parole would be her son’s death warrant.

By 1909, Thurman was no longer the sheriff. He had left law enforcement and opened up Thurman’s Sash and Door Company. Thurman must have thought long and hard about the matter when approached by Mrs. Hammond; after all, he still had the scar in his hand from the wound he had received when her son tried to shoot his way out of the Madera jail eight years earlier. Thurman remembered the day well.

It was late in February 1901, when Leonard Hammond walked into the saloon of the Vignolo Hotel in Berenda, The rooms were all occupied, and the bartender was having a time keeping up with the requests for libations. Business in Berenda had been brisk; the town had become the hub of a lively trade that radiated out in all directions from the little railroad burg north of Madera.

Hammond walked unnoticed into the saloon, stepped up to the bar and ordered a drink. As he took the glass with one hand, with the other he slid a pistol from under his belt and held it concealed beneath his overcoat. At just the right moment, Hammond backed away from the bar and proceeded to inform his fellow patrons that he was going to relieve them of their valuables.

The element of surprise was on the side of the young robber. All of the patrons did as they were told and lined up against the wall. Holding the crowd at gunpoint, the thief beat a hasty retreat. One of the patrons was immediately dispatched to Madera to alert Sheriff Thurman. In turn, Thurman assigned Constable Herman L. Crow to bring the fugitive to justice.

Crow did his job, and in a short time he was escorting Hammond to jail. Deputy Erving R. Lewis was on duty at the time and took custody of the prisoner. Forgetting that Hammond was not only crooked but cunning as well, Lewis granted the prisoner’s request to take a bath.

It seemed innocuous enough; however, it just so happened that the bath was on the middle floor of the jail’s turret. Lewis gave Hammond not only a towel but also enough soap and time alone to work one of the bricks in the wall loose.

When Lewis went back upstairs to return the prisoner to his cell on the bottom floor, the criminal hit the lawman over the head with a brick he had wrapped in a towel.

Grabbing the officer’s gun, Hammond ran downstairs only to find the main door locked. Lewis, in the meantime, ran to the ladder and reached the top floor of the turret, closing the door behind him so the prisoner could not gain access to that part of the jail.

The standoff continued until Thurman came riding by the jail on his bicycle. Lewis, who had been watching from the window at the top of the turret, yelled out, warning the sheriff of the situation.

Thurman rushed to the front door with complete abandon, and when he opened it, a fusillade of shots from the pistol Hammond had taken from Lewis peppered around him. The robber got lucky and nicked Thurman in the hand, whereupon the sheriff wounded the prisoner twice — once in the stomach and again in the left eye. That final hit ended the duel, and Hammond went back to his cell.

On April 1, 1901, Madera County’s first Superior Court Judge William M. Conley gave Hammond the 90-year sentence, never expecting that he would ever be released. He reckoned without, however, the determination of a mother.

In 1909, when Mrs. Hammond came back to Madera seeking a parole for her son, Thurman was not the only Maderan she descended upon. She enlisted the sympathy of a number of prominent local citizens on behalf of her son, and was successful in many cases. Thurman himself confessed he fell to the woeful pleadings of the convict’s mother. On Nov. 1, 1909, Hammond walked out of Folsom a free man but doomed nevertheless. Remember, he was incorrigible.

On July 6, 1912, Hammond decided to hold up a Sacramento River boat near Irish Landing. As he held the gun on the crew, the boat’s captain tackled Hammond and threw him overboard. When he rose to the surface, Gus Nelson, one of the crew, slammed his brains out with a boat hook.

Meanwhile, on Saturday, July 13, 1912, William B. Thurman opened up his Madera Tribune and saw on the front page how his old nemesis had “missed the boat,” euphemistically speaking. One wonders how much his signature had to do with Hammond’s parole?

Comments